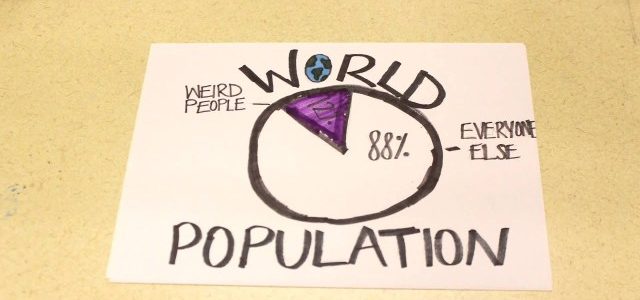

We’re Weird; Not Everyone Is

We at Mobus Creative Negotiating have warned against the assumption that everyone is just like us – whatever the minor differences in taste and preferences, we all think and feel along pretty much the same lines.

Wrong. Joseph Heinrich, chair of Harvard’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, explains why in The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous (Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2020, $35). He shows that we WEIRDos – Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic – are the exception in human history, and lots of people today approach life in an entirely different manner than we do. What he says about policymakers applies to negotiators: “When [we] infer how people in other societies will understand their actions, judge their behavior, and respond, they tend to assume perceptions, motivations, and judgments similar to their own.” His warning about economists applies equally to negotiators: we have “a way of thinking that has little place for culturally-evolved differences in motivations or preferences, let alone differences in perception, attention, emotion, morality, judgment, and reasoning.”

His criticisms extend to psychologists. The standard view among psychologists has been that people have five basic personality dimensions: how much they are adventurous, self-disciplined, extraverted, compassionate, and emotionally stable. Heinrich shows how those are the characteristics of WEIRDos but not that of other peoples around the world. For instance, in many farmer-forager societies, the basic personality split is between those who are work hard at productive activities and those who build a rich network of social relationships – a division which in no way corresponds to the model psychologists developed by studying WEIRDos.

Much of Heinrich’s account is about how the West’s evolution broke down the intensive kin-based institutions which prevail in much of the world. The West moved in the direction of voluntary associations, from governments to corporations. The process was slow; for centuries, these voluntary associations were often usurped by large, powerful families operating on the older based of kin-based relationships. As he explains, “With the declining importance of relationships and kin-based institutions, cultivating a personal reputation for hard work, efficiency, self-control, patience, and punctuality became more important.”

Those are not universal human values; they are the values of we WEIRDos. We should not be surprised if, when negotiating with people from other cultures, we find they pay little attention to such things.